A tale of two Jasons: the best and worst of social commentary in music.

Two Southern musicians tackle the urban-rural divide…with wildly different results.

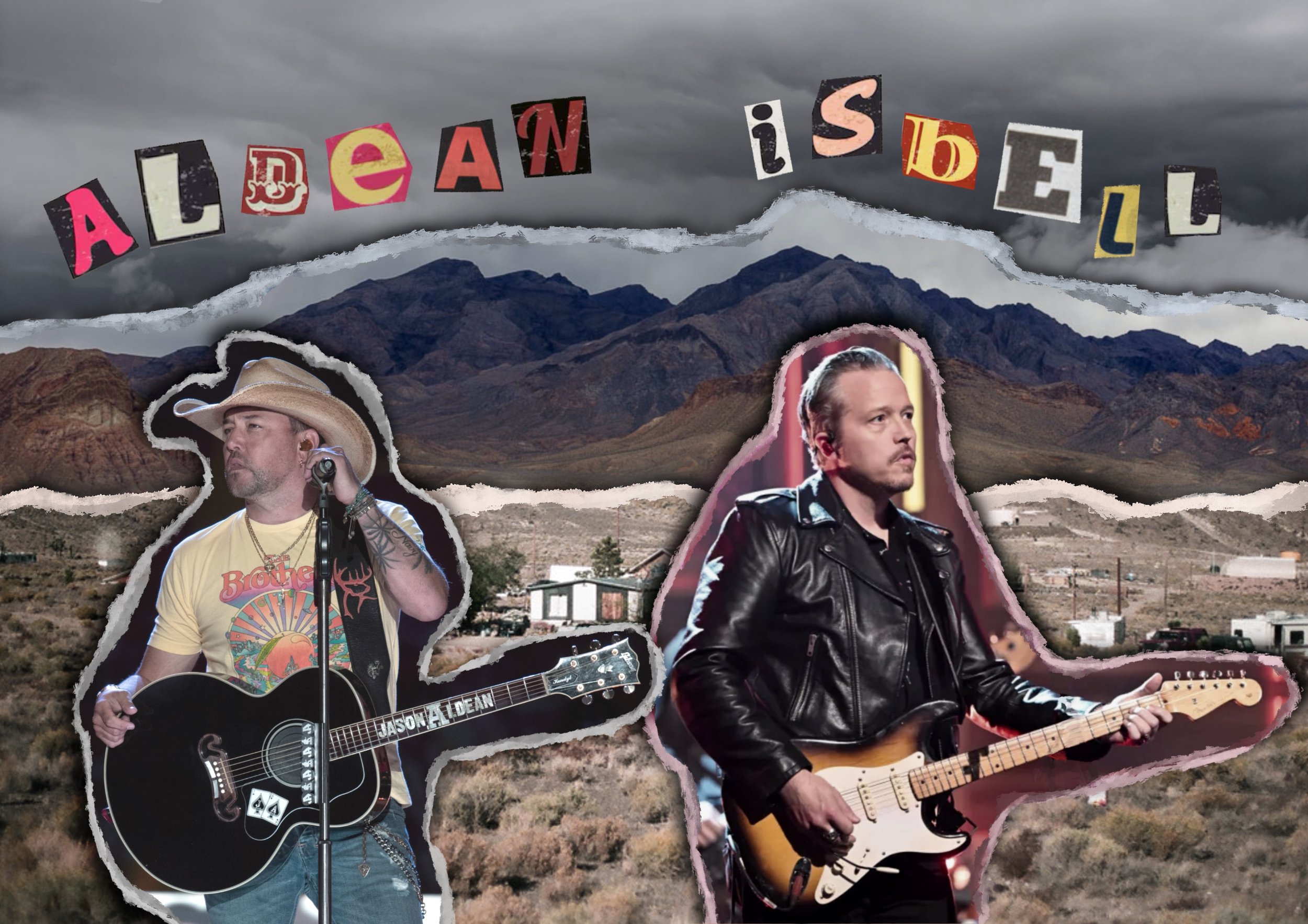

artwork by Tanaya Vohra.

If I had a nickel for every time a prominent Grammy-nominated Southern musician released an indictment of big-city values in the last seven years, I would have at least two nickels—but it really isn’t strange that it happened twice. After all, the rural-urban divide is the clear centerpiece of this generation’s conception of the American culture wars. At its best, such framing helps draw attention to the slow death of small-town economic opportunity and the hollowing out of tight-knit rural communities. At its worst, it perpetuates dangerous myths about race, poverty, and crime that further polarize us. Either way, it should not be surprising that politically-minded rural musicians might find themselves tempted to add their two cents to the discussion.

But do you know what is strange? Both of these critiques come from people named Jason, each a near-perfect illustration of the good and the bad that comes out of a focus on these “two Americas.” While Jason Isbell and the 400 Unit’s “Last of My Kind” tells a nuanced and emotionally poignant story about losing oneself in a sea of strangers, Jason Aldean’s “Try That in a Small Town” offers nothing but faux outrage through race-baiting headlines and tired clichés.

As a cursory Google will show, these tracks were made with very different ambitions in mind. “Last of My Kind” opens The Nashville Sound, Isbell and co.'s Grammy-winning 2017 record, but it has no music video and was written by Jason based on the personal experiences of “the people [he] grew up around.” Aldean’s wannabe-power-ballad, on the other hand, was written by a group of professional songwriters as an attention-grabbing single accompanied by a video filmed at the site of a famous lynching. Clearly, only one of these tracks has any discernible emotional center, and this notion is only further borne out upon closer listening.

Let’s begin with “Try That in a Small Town.” Within the first ten seconds, you can immediately notice the heavy use of pop elements in the production, complete with electric clapping sound, as Aldean pulls headlines from tabloids: “Sucker punch somebody on a sidewalk/Carjack an old lady at a red light/Pull a gun on the owner of a liquor store.” He conjures images of lawlessness and danger in the inner city, drawing upon patriotic anger as he rails against BLM protestors who “Stomp on the flag and light it up” and responds, “Yeah, ya think you're tough.” The instrumental overwhelms you with overlapping electric guitars while Aldean spits vitriolic threats on the chorus:

Well, try that in a small town

See how far ya make it down the road

'Round here, we take care of our own

You cross that line, it won't take long

For you to find out, I recommend you don't

The entire work is centered around thinly veiled undertones of machismo racial violence: the second verse’s mention of “a gun that my granddad gave me” and the bridge’s reference to “good ol' boys, raised up right/If you're looking for a fight” are both pretty damn obvious. On this track, Aldean is angry, and he wants you to know it. While “that shit might fly in the city,” the big, strong men in his hometown will deal out justice with their own two hands! Never mind that the lyrics glorify a sort of extrajudicial violence that sounds suspiciously like lynching, or that he literally filmed the music video at a lynching site: this song is just about protecting our country from violent criminals! Who is Aldean referring to as "our own," and what does he mean by "raised right"? Who knows!

Blatant dog-whistles aside, what makes this track particularly insufferable as a work of social commentary is its total lack of an authentic human core. Since Aldean did not even write this song himself—as Isbell himself pointed out—it makes sense that he fails to bring a unique perspective to the issue. Put any macho-looking country crooner in his shoes: nothing about the song would change. Victim, perpetrator, and “good ol’ boy” alike are all reduced to painful caricatures that exist only as a vehicle for the “us-or-them” narrative. The lesser Jason laments the inhumanity of street crime, and yet he seemingly forgot his humanity at home.

Now that you have seen what the worst of “anti-cityscape” commentary looks like, we can move on to discuss the best. Where Aldean tries to project power and confidence with heavy production, “Last of My Kind” opens with a soft acoustic guitar only occasionally colored with other strings or a light brushing on the drums and keyboard. Paired with Isbell’s soulful, weather-beaten vocals, the resulting texture feels intimate and vulnerable. The opening lines “I couldn't be happy in the city at night/You can't see the stars from the neon light” are strikingly mundane and personal. His focus is not some provocative political angle, but instead the little things that one loses when they leave the countryside. The Alabama native’s trademark narrative style is simple yet vivid enough that one can genuinely imagine him walking down a Chicago street for the first time, gazing out at the dirty rivers and sidewalks with something halfway between wonder and disappointment.

Perhaps the most notable difference is that Isbsell approaches his criticism from a place of empathy and love. His core complaint is that modern city has become inhospitable and impersonal, drained of its soul by sheer scale:

So many people with so much to do

Winter’s so cold my hands turn blue

Old men sleeping on the filthy ground

They spend their whole day just walking around

Nobody else here seems to care

They walk right past ‘em like they ain't even there

Am I the last of my kind?

When you live in a city long enough, you grow numb to routinely walking past homeless people. Here, Isbell’s outsider perspective allows him to point out just how depressing some of these aspects of normal city life are without resorting to stereotypes and shock value.

Even the villains of the track’s narrative are otherwise normal college students singling out someone that doesn’t fit in, and that makes their cruelty all the more disheartening. Isbell’s protagonist describes how “Everything I said was either funny or wrong/They laughed at my boots, laughed at my jeans/Laughed when they gave me amphetamines.” Our hero finds himself drugged and dumped in the most dangerous neighborhood in the city—confused and alone in a place he doesn't belong.

That moment is a microcosm of the entire story. At its core, “Last of My Kind” is about losing that sense of belonging. In the face of economic pressures and the relentless march of time, we lose parts of ourselves that we can’t get back. We learn to not look twice at the man on the street corner. We learn that the easiest way to survive the superficial judgment of others is just to blend in and follow the crowd. We forget the simple beauty of a sky full of stars or the deep blue of clear water. And then one day, we look back and realize that there is nothing left of our past to return to. It has fallen victim to our society’s desire for infinite growth, devoured in the endless churn of expansion, destruction, and renewal:

Daddy said the river would always lead me home

But the river can't take me back in time and daddy's dead and gone

And the family farm's a parking lot for Walton's five and dime

Am I the last of my kind?

Compelling social commentary—and compelling music in general—is borne from sincere emotion and the weight of personal experience, for the beauty of music is its unparalleled ability to capture and communicate the raw depths of our inner selves. With “The Last of My Kind,” Isbell weaves life and legend together into a compelling human story, and his consistent mastery of the liminal space between the two is why so many music critics name him among America’s greatest living songwriters. Bombastic production and appeals to shock and outrage may be enough to make a hit record, but they are no substitute for the authenticity and vulnerability required to craft something truly meaningful. On that front, one Jason would do well to leave from his spiritually empty path and instead follow in the footsteps of the other.

edited by Kristen Wallace.

artwork by Tanaya Vohra.