Music in the Mediterranean: sonic echoes from shore to shore.

A dive in the Mediterranean Sea, its wrecks, and underwater tunes.

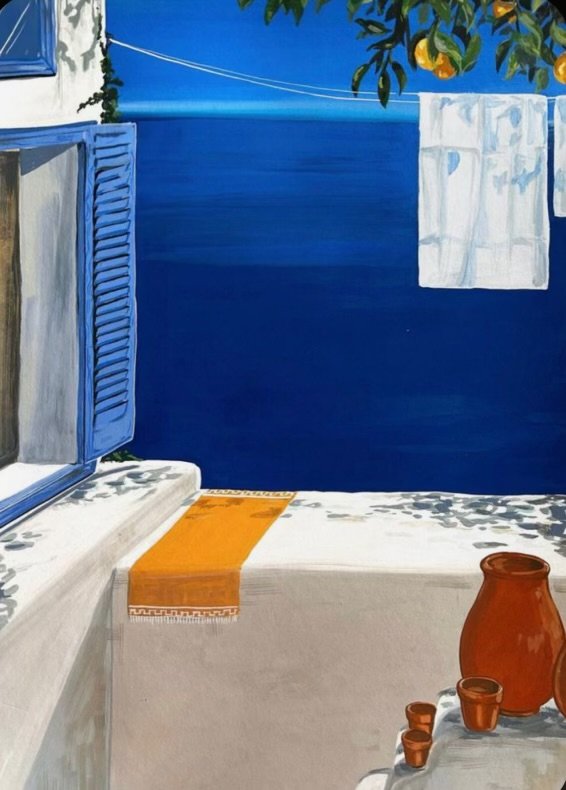

artwork by Charlotte Henderson.

As the relationship between music, culture and geography becomes more and more complex in a globalized world, how does one make sense of new cultural and musical trajectories which cross over the fixity of geopolitical borders?

The horrific unfolding events in Gaza serve as yet another reminder of the political fraughtness of the Mediterranean Sea as a geopolitical space. The routes of boats leaving the North African coast filled with refugees slash its surface. Borders become unsurpassable walls, shattering the unity of a three-continent-wide Mediterranean identity. These wounds remain, but not for nothing.

Emerging artists have found great inspiration in the Mediterranean Sea as a space of war, inequality, but also of great cultural interconnectedness. As wounded as this infamous Sea is, artists turn it into a fertile land for musical production. In an attempt to overturn political walls, they draw new musical trajectories over and across prescriptive geographical boundaries.

Nu Genea’s 2022 album Bar Mediterraneo is the quintessential expression of this project. Born nine years ago in Naples/Berlin as an artistic project of musicians Massimo Di Lena and Lucio Aquilina, Nu Genea has quickly grown into a cornerstone of the contemporary Italian and international music scene. The dual geographic origin of the project between Naples and Berlin introduces the theme of diaspora, which often comes back in the tracks. Both living in Berlin, Di Lena and Aquilina started Nu Genea as a way to collect “the sonic echoes that, down the centuries, have touched the shores of Napoli, their hometown.” In 2018, the project adopted Fabiana Martone’s deep vocals in its jazz-funk sound. In the warm-colored world of Nu Genea, music becomes a way to reconnect to one’s homeland and showcase its undertones.

This intention clearly comes through in their earlier album Nuova Napoli. The first track, sharing its name with the album title, draws the picture of a “Nuova Napoli” (New Naples), almost in the act of (re)imagining oneself in an unrealistically ideal recollection of one’s home. It is clear, after all, that there’s a reason why Di Lena and Aquilina decided to move to Berlin. Stuck in between a sense of homesickness and the necessity to leave, “Nuova Napoli” recounts Naples in its contradictions and undeniable charm.

Every song on the album is in Neapolitan, a powerful choice revealing the artists’ desire to re-establish an intimate connection to their hometown. Moreover, given how stigmatized Southern dialects are in Italy—Neapolitan especially—the choice to have every song in dialect almost comes across as political. It is a re-appropriation of the language of their parents, as well as an act of subversion of standard Italian as the status quo. By the end of the album, this sense of homesickness culminates in the last track “Parev’ajer” (It seems like yesterday); however, this sense of longing doesn't diminish the track's funky disco sound—if anything, it enhances it. Thinking back to the childhood spent in their hometown, the song reflects on the wistful sense of nostalgia stirred by those memories.

Zooming out from Naples as their inspiring muse, Nu Genea released Bar Mediterraneo in 2022. As the title suggests, this second album builds on the cultural interconnectedness of the Sea and its people, mirroring the naval trading routes of the past. As those sonic echoes touch the shores of Napoli, Nu Genea amplifies them back into the rest of the globe. Unlike Nuova Napoli, which exclusively uses the Neapolitan language, Bar Mediterraneo adopts Neapolitan, Italian, Arabic, and French in its nine tracks. While many more languages could be used, this begins to compose the cultural diversity of a Mediterranean Sea that speaks to itself in multiple languages and its willingness to listen even when it doesn’t understand.

The tracks in Arabic and French, “Gelbi” and “Marechià” respectively, both feature other artists. The vocalist in “Gelbi” is Marzouk Mejri, a Tunisian percussionist currently living in Italy, while “Marechià,” which has both French and Neapolitan lyrics, is performed by French-Cameroonian singer, Célia Kameni. The inclusion of multiple languages in Bar Mediterraneo is a way to prompt a Mediterranean dialogue, which doesn’t need official documents to travel across the Sea. The linguistic dynamic becomes especially curious in “Marechià,” which starts in French and switches to Neapolitan in the second verse. The change is so smooth that even Italian listeners, who don’t speak French or Neapolitan, would struggle to recognize them as different languages. This playful yet intentional detail underscores the direct interconnections between Mediterranean cultures and seeks to prompt a generative dialogue about these similarities.

I had the privilege to see Nu Genea live last August in Milazzo, Sicily. While lead vocalist Martone didn’t attempt the Arabic in “Gelbi,” she did perform “Marechià” in both Neapolitan and French. It was heartwarming to see the cross-cultural layers of their music unfold live. On top of that, their energy was crazy, as they jumped on the stage cheering the crowd on. While Nu Genea’s jazzy vocals are definitely one of the strengths of their sound, a few parts of the set were instrumental. This highlighted the band’s technical abilities, as they performed convoluted guitar solos and mixed electronic loops, never losing their authentic Neapolitan sound. The Milazzo Castle—venue where the concert took place—offered an overlooking view of the Sicilian northern coast. Reaching out in the sea, it seemed as though Nu Genea’s sounds could echo all the way to the farthest Mediterranean shores.

artwork by Charlotte Henderson.

It is down there in Sicily that this article continues. Historically conceptualized as the bottom edge of Europe, Sicily has always had to turn, face, and speak northward. However, escaping a Eurocentric framework in place of a Mediterranean one recodes the island as central, letting it speak in all four directions. The night I saw Nu Genea live in Milazzo, they had two bands open the concert for them. One of them was especially connected with the place where they performed.

French four-piece Crimi started their set by thanking the festival organizers for giving them the opportunity to perform in a land they love so dearly. Indeed, not only do they perform all of their songs in Sicilian, but the very existence of Crimi is due to “frontman Julien Lesuisse’s desire to rediscover his Sicilian heritage.” Like most people, I purchased my ticket to see Nu Genea, not even paying attention to the opening bands. However, Crimi’s unusual and groove sound instantly caught my attention as I entered the well-lit outdoor venue. On top of that, I was intrigued by the language of the lyrics, which I failed to understand, despite speaking Italian. It took me a Google search to figure out that it was Sicillian they were singing in. This only goes to stress how many different cultural and linguistic sub-realities there can exist in one half of the same country—and how beautifully they might intermix with other influences.

Having grown up in Lux, Eastern France, Lesuisse spent his childhood divided between Sicily and Bourgogne-Franche-Comté, which exposed him to other immigrant communities in France. In a deep dive into the blue waters of Sicily, Crimi explores the spaces, language and folklore that Lesuisse’s parents left behind. However, Sicily it’s just the start for Crimi. While the influence of Sicilian folklore is clear in their tracks—becoming central in the use of the Sicilian language—Lesuisse found sources of inspiration everywhere around him.

In Crimi’s debut album Luci e Guai, Lesuisse joins forces with a trio of musicians, Cyril Moulas (guitar), Mathieu Felix (bass), and Duval (drums), all three of them bringing new musical influences to the project, from Algerian raï to Ethio jazz. This shows in their most popular track on Spotify, “Mano d’oro.” The guitar riff starts the song, immediately setting the very distinctive groove of the track. The sharp baseline then jumps in and works with Lesuisse’s vocals to create a funk, almost rap-py, feeling. Despite the resolute and energetic sound of the track, “Mano d’oro” deals with the hardships of the immigrant experience, once again raising the question of diaspora.

“Amuri amuri quantu si luntanu” (Love, love, how far you are), Lesuisse sings; and then: “Vuliva jiri unni va la negghia” (You wanted to go where the clouds go), powerfully expressing the shattered sense of distance and missing of one’s dear ones and loved places. Lesuisse’s cross cultural exposure to other immigrant communities in his childhood certainly informs his stylistic choices. In this way, Crimi’s adoption of other genres like Algerian raï, as well as Afrobeats, highlights the idea of a multicultural Mediterranean identity, which rises from the diaspora of various communities across the sea.

After finishing their incredible set, Lesuisse thanked the audience and I could not help but notice that he did not sound fluent in Italian. That left me surprised: I assumed that he knew Italian since he’d been singing in Sicilian—his families’ language—the whole time. My reaction of surprise speaks to Crimi’s existence in a Mediterranean trajectory, which defies geographic and political prescriptions. Not only does Lesuisse’s Sicilian voice honor his family’s culture, but it also defies the homogenization of Italian cultures and rejects standard Italian as the correct version of the language. Tracing a direct line between Sicily and France, while leaving the rest of Italy unmarked, Crimi shows how cultural sub-realities continue to exist outside of the mainstream understandings of political entities.

As more and more of these trajectories are traced, the Mediterranean Sea becomes a complex web of relationships scribbled over a map. These waters exist as an exchange place of ideas, which surpass the fixity of geo-political borders.

If loud enough, music can do away with any wall.

And in times where people are forced within physical (or mental) borders, art is what we must turn to in the attempt to overturn them.

edited by Joseph Mooney, Editor-in-Chief.

artwork by Charlotte Henderson.