Crises in Classical Music: Heinrich Schütz and COVID-Era Concerts

The classical music industry has been drastically reshaped over the past year due to the COVID-19 pandemic, with some changes being for the better and many more for the worse. Restrictions and lack of funds have forced concerts to take on new forms and have put the limelight on often ignored repertoire. However, this is not the first time music has had to bend to the will of exogenous circumstances– the career of Heinrich Schütz (1585-1672) was impacted in a similar way by the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648). Schütz’s musical style was forced to adapt to economic constraints, much like musicians today. Schütz was, for most of his life, the Kapellmeister (court-composer) to the Elector of Saxony. Having studied under Giovanni Gabrieli (1554-1612) at Venice, Schütz picked up the famous polychoral style of cori spezzati (separated choirs) in which music is composed specially to create an echoing question-answer effect between different choirs occupying lofts on opposing sides of the nave. This resplendent style required quite an expensive ensemble–

Art by Shira Silver

Gabrieli even had brass bands playing in the choir lofts of St Mark’s Basilica in Venice. Schütz brought this popular style over to Germany and incorporated it at the famous Dresden Hofkapelle (court chapel).

However, even the admired Schütz had to bow to ill-fated exogenous circumstances. The Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648) led to a death toll of around eight million across Europe from battle, pillaging, religious persecution, and frequent resurgences of bubonic plague. Peasants and soldiers often had to go hungry for days, resorting to eating cats and dogs and even to cannibalism. Civilians were assaulted, women were raped, infants were slaughtered. States and nations across Europe emptied their treasuries. Schütz and the entire ensemble of musicians at the Duke’s Court in Dresden wrote to the Duke in 1625, saying “[we] are now entering the seventh quarter that we have not been paid.” Unfortunately, the Dresden Hofkapelle was stripped even further of funding in the coming years. Schütz wrote again to the Duke in 1641–

“Should our aforesaid collegium be left helpless in this way yet longer; or … should any of the very few persons still remaining die or otherwise become physically unable...; the restitution of the failed Hofkapelle ... would either be impossible or indeed certainly very difficult. Together with the losses over time, and without doubled or tripled expenditures, it might never again attain to that level.”

Schütz with his musicians in the Chapel of the Royal Palace in Dresden

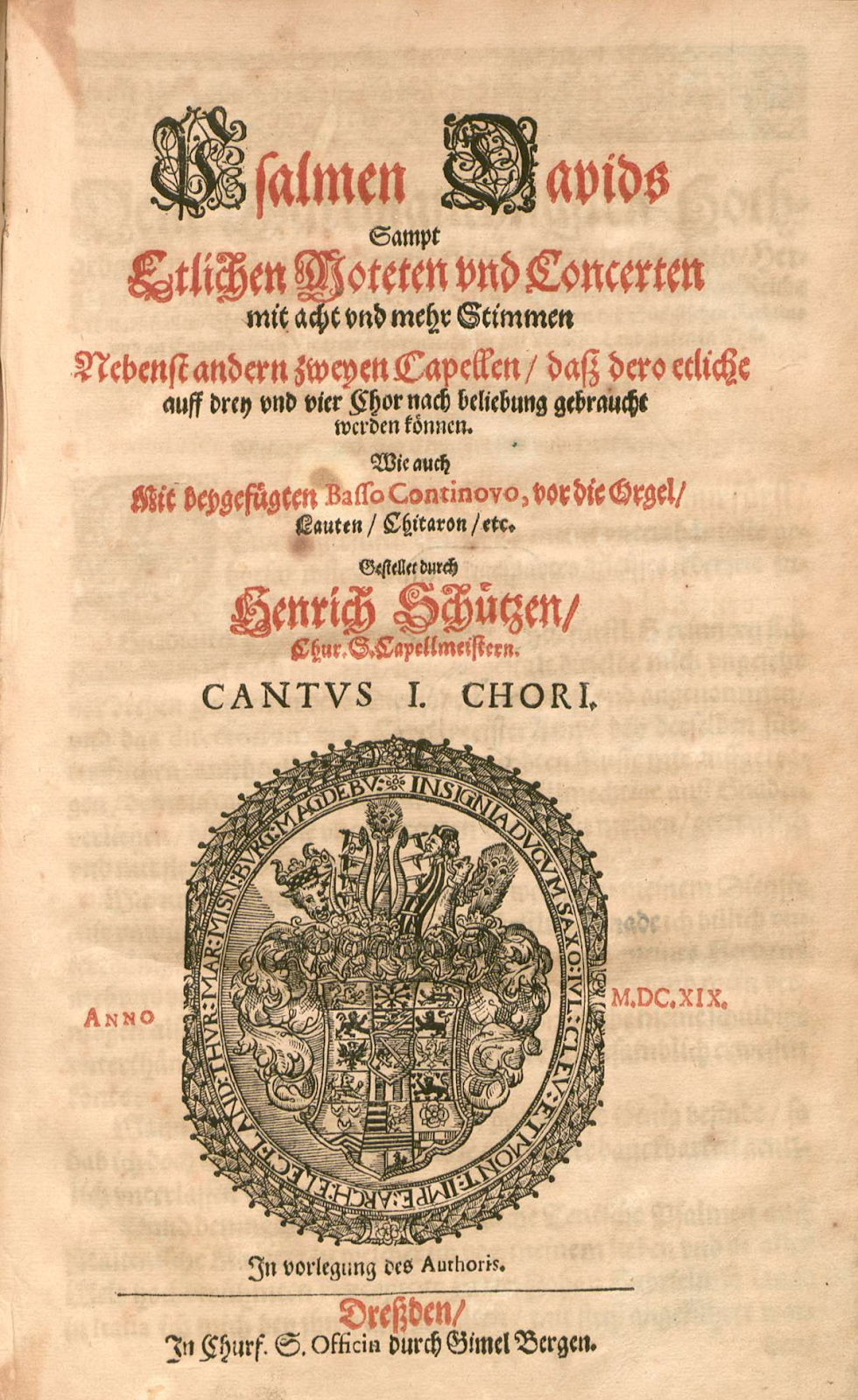

Schütz could no longer put on works in the grand Venetian style of cori spezzati, like his Psalms of David (1619), scored for three or four choirs along with accompanying instruments. Instead, we see an inward shift in his music. Schütz became more reflective, drawing parallels to the sad state of his world. His famous Musikaliche Exequien (1636) has only five voices (with three additional soloists joining for the last section, directed by Schütz to stand away from the accompanying organ– a faint resemblance to cori spezzati) and no obligatory instruments. Written for the funeral of a friend and patron, Schütz’s evocative setting of the texts urges listeners to seek solace in God during times of woe. His set of sacred concertos, the Kleine Geistliche Konzerte (composed around the same time), also stresses typically Lutheran tenets, which would have been close to Schütz’s heart. These, like the Exequien, are scored for very few voices and bass accompaniment.

Zoom ahead to 1650. The now sixty-five-year-old Schütz had lived through the harrowing Thirty Years’ War, which had finally come to an end. The restoration of the chapel choir allowed him return to the polychoral splendour of his early works with the Symphoniae Sacrae III, scored on an even grander scale than the Psalms of David. This collection, one of my favourites, showcases a varied palette of instruments including violins and cornetts which buzz around the prominent vocal forces in beautifulcounterpoint, creating an ethereal halo around the singers. Schütz alludes to the horrors of the Thirty Years’ War in one of the pieces, Saul, Saul, was verfolgst du mich?” The voice of Jesus is represented by two separated choirs, whose clamouring calls to Saul (later the Apostle Paul) increase in intensity as the piece progresses. A third choir persistently reminds Saul to not persecute Christ. Schütz is clearly evoking the persecution of Protestants in Catholic nations during the war. The Symphoniae Sacrae III were considered by Schütz to be the culmination of his career in Dresden. Six years later he retired from his official capacity as Kapellmeister, living out the rest of his life composing for special occasions and personal projects.

Psalmen Davids (1619), cover page

Schütz’s life and career are echoed by the tribulations classical music faces today. Like the celebrated players of the Dresden Hofkapelle in the 1620s, the players of the acclaimed MET Orchestra of New York found themselves without pay for more than eight months from April 2020 due to COVID-19. Like the change in Schütz’s musical output during the war, classical music performance in the time of COVID revolves around masked, socially-distant concerts available to audiences via livestream only. More attention has been given to smaller chamber works, while orchestral masterpieces, opera productions, and other large-scale works have been temporarily shelved.

While experiencing a concert from home on one’s computer might not be ideal, live-streamed concerts have catered to the larger public, being more affordable and intimate than ones held in concert halls. The past year has given musicians and their audiences everywhere a chance to find consubstantiality with each other, much like Schütz’s more poignant pieces written during the Thirty Years’

Symphoniae Sacrae III (1650), cover page

War did. A touching example of this is musicians from the Houston Symphony performing virtual recitals for lonely patients, and aiding in their recovery as a result.

As the world begins to gradually reopen, the potential return to in-person concerts is exciting. Just as the Symphoniae Sacrae III summed up Schütz’s composing career and allowed him to express angst bottled-up over the course of the Thirty Years’ War, I foresee many grandiose concerts commemorating the hundreds of thousands of lives lost to COVID-19. At the same time, I hope initiatives like the Houston Symphony’s virtual concerts for patients are continued. After all, Heinrich Schütz’s war-time compositions and COVID-era concerts are just two examples, among many, of music helping artists and listeners to heal and grow as human beings.

Bibliography

Hardy, Michael. 2020. “Chopin Versus the Coronavirus: Classical Music is Helping Houston Patients Heal.” Texas Monthly, December 21, 2020.

Hoffer, Brandi. “Sacred German Music in the Thirty Years’ War.” Musical Offerings 3, no. 1 (Spring 2012)

Johnston, Gregory S. Letters and Documents in Translation- A Heinrich Schütz Reader. Oxford University Press, 2013.

Recommended Albums

Psalmen Davids- https://open.spotify.com/album/2ECpNPPwTGPhKqcr2NoYYj?si=mhztshMLTUGejVa1jNrm4w

Musikaliche Exequien (plus pieces from the Geistliche Chormusik and Kleine Geistliche Konzerte)

https://open.spotify.com/album/02W4TQQxc5KHObxtB2npCX?si=zWdST1f2RbiY53rcud7VsQ

Geistliche Chormusik- https://open.spotify.com/album/5cdNeLOO3IVhmoxzCEn2xP?si=CnbUzikTS4qSds7FhKBbwg

Symphoniae Sacrae III- https://open.spotify.com/album/4xo17AIKx7qMp6BDMNLs6K?si=NbU5H9PlRiqOZUrafidc0g

Edited by Maia Driggers, editor of Music History

Cover art by Shira Silver