Josquin des Prez: musical brand name.

2021 marks the 500th anniversary of the death of superstar Franco-Flemish composer, Josquin des Prez (1450/55-1521), popularly known by his first name. Extremely influential in his life, Josquin’s work shaped many genres of music for centuries afterwards. Late 16th century theorists like Gioseffo Zarlino would cite his work as exemplary. Even Martin Luther, a rough contemporary of Josquin, praised his work, writing that "he is the master of the notes. They must do as he wills; as for the other composers, they have to do as the notes will." Josquin is also partly responsible for the preservation of many of his contemporaries’ music, because of the influence he had on 16th century print culture.

Born in modern-day France or Belgium, Josquin learned from the acclaimed composer Johannes Ockeghem, and subsequently had an illustrious career in Italy. After a brief stint in Milan working for the ruling Sforza family, Josquin worked in the Papal Choir in Rome, one of the most prestigious jobs in music at the time. Being a foreigner, he got exposure to secular Italian music in Milan and sacred music in Rome. These cities shaped his writing style into that of a mature composer and explain his decision to eventually return to Milan for a few years, then back to his homeland of France around 1498-99, by which time he had become famous across Europe.

1502 proved to be a landmark year for music history. The Italian printer Ottaviano Petrucci published the first printed music book featuring music by just one composer – Josquin. This was the Liber primus missarum Josquini (“The First Book of Masses by Josquin”), containing many settings of the Mass ordinary by Josquin, including his Missa L’Homme Arme, based on the famous medieval French hunting tune L’Homme Arme (The Armed Man). Petrucci, as well as other printers, would find Josquin’s works to be extremely lucrative in coming years. The composer’s growing reputation as a genius corresponded to a high demand for copies of his music for perusal and performance.

Figure 1: From the Liber Primus Missarum Josquini, printed by Petrucci

That year, Josquin was also hired into the court of Ercole d’Este, the Duke of Ferrara. A famous anecdote follows: Duke Ercole was advised to hire Josquin’s contemporary, Heinrich Isaac, because Isaac was “more sociable” and “composed better.” Josquin, on the other hand, “composes better” but “only when he pleases, not when he is requested to, and has demanded 200 ducats in salary, while Isaac is content with 120.” Josquin was hired nevertheless, partly because of a promise to immortalize the duke through his music. Three years later, Josquin’s second volume of masses published by Petrucci included his Missa Hercules Dux Ferrariae (Mass for Hercules, Duke of Ferrara), following up on that promise. This piece is well-known due to Josquin’s efforts to imitate his master’s name and title in the solfege used for the main theme of the mass. Josquin uses the syllables ‘Re-Ut-Re-Ut-Re-Fa-Mi-Re,’ which imitate the vowels of ‘Her-cu-les dux fer-ra-ri-ae’. (‘Ut’ became known as ‘Do’ - the old system of hexachords had syllables ‘Ut-Re-Mi-Fa-Sol-La,’ which then became the ‘Do-Re-Mi…’ we know today.) This story gives us a brief glance into Josquin’s fiery temperament – probably the earliest composer about whose character we can discern.

Josquin was known in his time to be a master of word-painting, musically highlighting specific words in the text to bring out their literal or metaphorical meaning. While this wordplay was a natural feature of secular chansons and madrigals, Josquin was adept in using this colorful technique even in sacred music. One of my favorite motets of his, the posthumously published Huc me sydero, is a good example. Josquin builds a beautiful imitative texture in the five voices. Downward flowing melodies on the word descendere (“come down”) and syncopated, repeated ideas on verbera tanta pati (“to suffer such blows”) creates a resplendent vision in the mind of any listener familiar with Latin. Contemporary listeners, especially literate noblemen, would recognize and appreciate Josquin’s musical puns (Catholicism, and by extension Church Latin, being a central force in European life).

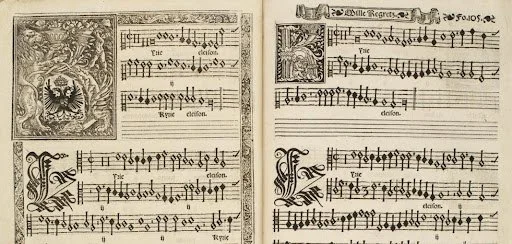

One of the most well-known works attributed to Josquin is a simple four-part chanson, Mille Regretz. It is hauntingly sweet, expressing immense grief on parting from one’s beloved. Josquin uses the Phrygian mode which, with its lowered second, is traditionally associated with pain and sorrow. The ending is particularly striking because the melody ends on an unexpected minor third, instead of the more typical major third, expressing an aching sonority. Even after his death, Josquin’s name was a claim to fame. Mille Regretz was adapted by many subsequent composers into their own settings. The Spanish composer Luis de Narvaez (d. 1549) wrote variations on the theme for vihuela (a plucked string instrument) while in the service of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain. The Mille Regretz theme was supposedly a favorite of Charles’, and Narvaez’s setting was originally titled “La Cancion del Emperador” in his honor. Associations with Charles V are just as strong in Cristobal de Morales’ 1544 publication of his mass based on Mille Regretz – the illuminated ‘K’ of the word ‘Kyrie’ in the original partbook is decorated with Charles’ emblem, the two-headed eagle.

Figure 2: Cantus part from Morales' Missa Mille Regretz, with double-headed eagle of Charles V (via Morales Mass Book)

However, there is still speculation on whether Mille Regretz is authentically a Josquin composition, since many chansons were falsely attributed to him. While Josquin worked primarily with Petrucci, a French printer, Pierre Attaignant, invented a less expensive and quicker method of printing music. Attaignant pumped out collections of chansons, masses, motets, and madrigals at a rapid pace, including five books of chansons by Josquin. While Attaignant’s press was of lower quality than Petrucci’s, it was a much more feasible option for up-and-coming composers who wanted to get their work printed and proliferated at minimal cost. Many of these composers falsely attributed their work to Josquin, knowing that collections under his ‘brand name’ would sell much better. As a result, we do not definitively know the authorship of many compositions printed using Attaignant’s press.

Figure 3: Attaignant’s lower-quality print (via WalterBitner.com)

Josquin was truly one of the earliest musical ‘brand names’, with his music being held in esteem by contemporary and later composers, theorists, nobles, commoners, scholars, and laymen alike. His musical abilities aside, the influence he had on 16th century print culture has helped us learn about not only his work, but that of many unknown and unfunded composers. Josquin is the first composer for whom technology was essential to his success. Without printers like Petrucci and Attaignant, Josquin would probably be a footnote in the treatises of his immediate successors, with much of his work– and that of many of his contemporaries– lost to time. Not much has changed: artists today need good producers and services to distribute their work and achieve recognition. Josquin was the first, but not the last, to experience this symbiotic relationship between musical mastery and technological proliferation.

References:

Burkholder, J. Peter, Claude V Palisca, and Donald J Grout, A History of Western Music (9th Edition) (New York, NY: W.W. Norton and Company, 2014), 203.

Richard Taruskin, The Oxford History of Western Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 172.

Rob C. Wegman and Richard Sherr, “Who Was Josquin?” in The Josquin Companion (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 21-25.

Edited by Maia Driggers, editor of Music History

Cover art by Wyatt Warren