Monteverdi’s Venetian Years: The “Real Sun” of Opera

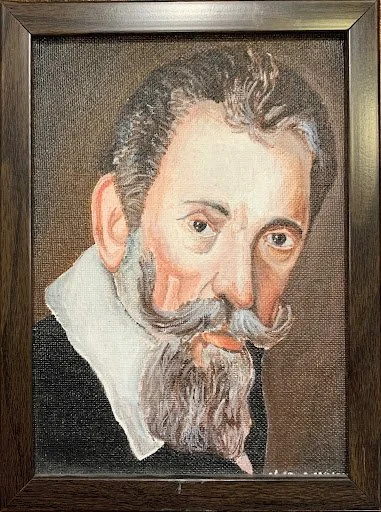

Art by Aatman Vakil

It’s Venice, 1639. You are excited as you take your seat in the magnificent Teatro Santi Giovanni e Paolo. Local legend Claudio Monteverdi has finally returned to his pet genre, opera, after a hiatus of 31 years. You have been attending these new, public operas for a couple of years now. While you have no reason to complain about the operas you have heard so far by young men like Francesco Cavalli, Francesco Manelli, and Benedetto Ferrari, you cannot help but predict that Monteverdi is about to blow them out of the canals. An enrapturing string sinfonia marks the beginning, and you cannot avert your attention for the next three hours as the story of Ulysses’ return to his homeland unfolds before you.

When Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643) relaunched his operatic career with Il Ritorno d’Ulisse in Patria (The Return of Ulysses to his Homeland) in 1639, he made a huge splash in the Venetian music scene. Public opera first came to Venice in 1637. During this time, new and up-and-coming composers, including Monteverdi’s pupil and right-hand man, Cavalli, hogged the stage. These operas were excellent, as were their composers (Cavalli would eventually reach international prestige in his career), but echoes of Monteverdi’s early operas were still fresh in the public’s mind due to their extraordinary depiction of human emotion.

It was only later that the elderly Monteverdi, then the director of music at St Mark’s Basilica in Venice, was lured out of operatic retirement with a libretto (operatic text) written just for him by nobleman Giacomo Badoaro. Badoaro was a member of the elite Accademia degli Incogniti (Academy of the Unknowns), which had supported literature and culture in Venice since its inception in 1630. [i] Monteverdi couldn’t resist the challenge and plunged back in. Making many modifications to Badoaro’s libretto, he composed Ritorno to premiere in the 1639-40 carnival season. His last opera had been L’Arianna, written for the Ducal court in Mantua way back in 1608. Both L’Arianna and its predecessor, L’Orfeo (1607) were huge hits and firmly established Monteverdi as an early bastion of operatic genius.

Ritorno, however, was a whole new ball game. While employed at Mantua, Monteverdi had access to well-trained musicians, functional instruments, set designers, and more. The themes and dialogues of L’Orfeo and L’Arianna were more embellished and catered to a noble audience of elites. In contrast, Ritorno was written for the Venetian public. The Incogniti openly espoused libertine morality, [ii] and while Ritorno has nothing explicitly debauched, it is full of humour which would have been inappropriate at Mantua. Monteverdi also had to scale down the instrumentation, writing for only a small string band and a few other instruments for the harmony. Even with all these constraints, Ritorno was extremely well-received in Venice (it was revived the very next year, a rare feat) [iii] and even exported around Italy. Musicologist Tim Carter writes of the fantastic production: “The opera has enough sex, gore, and elements of the supernatural to satisfy the most jaded Venetian palate… a ship turned into stone, Ulisse transformed in a flash of lightening, and an eagle flying overhead must have impressed the gallery.”[iv] This resounding success among both intellectuals and commoners prompted Badoaro to credit Monteverdi, saying that his Ulysses owed a greater debt to Monteverdi than the actual Ulysses did to the goddess Minerva.

The opera has a colourful cast of human and divine characters, who are often caricatures of virtue and vice. The plot covers Ulysses’ return to Ithaca at the end of the Odyssey. He is assisted in this venture by Minerva, his son Telemachus, and the loyal shepherd Eumaeus. They help him to vanquish the suitors wooing his chaste and loyal wife Penelope, and finally convince her that he is truly her husband returned to her after two decades apart. The straightforward themes of the opera, “the rewards of patience, the power of love over time and fortune – are clearly prepared in Monteverdi’s prologue.”[v] These are significantly revisited throughout the opera. Monteverdi employs tonal allegory at its finest, using tonal-hexachordal associations with characters and themes to tie them with the four figures of the prologue – Time, Fortune, Love, and the embattled Human Frailty.

Musically, the opera has many touching elements. Penelope’s opening monologue opens her heart to us as she sings of her loneliness. Throughout the opera, she only sings recitative [1] , emphasizing her grief. It is only in the final scene when Ulysses finally convinces her of his identity that Penelope casts away her recitative, and her primary key of D-minor (associated with Human Frailty), and sings a lyrical aria. Hero and Heroine sing together only in this final scene as the opera concludes with a heart-warming duet. Meanwhile, the Gods’ lines are more melismatic and musically verbose, demonstrating their vainglory. Monteverdi also accords lower class characters important musical roles; the glutton Irus, the servants Eurymachus and Melantho, and the nurse Euryclea all play significant parts in developing the plot. Irus especially is rhetorically profound when he shocks the audience by committing suicide in Act III after a comic, and seemingly superfluous, role. His musical lines, though a caricature, show some degree of authenticity in expressing the poor glutton. With raucous laughter over a dancing bassline, frenzied stammering, and sobbing desperation, Monteverdi plunges this comic character into suicide. Irus justifies his own suicide by calling hunger his ultimate enemy; eluding this hunger (via suicide) would therefore be a great victory. Such a stunning depiction of death played right into the Incogniti’s aim to uncover the meaning (or lack thereof) of death. [vi]

Poetically, Monteverdi’s hero Ulysses’ return home mirrored the aging composer’s return to opera. In the next few years, he would compose Le Nozze d’Enea con Lavinia (The Marriage of Aeneas to Lavinia) for the 1640-41 season [2] and his ultimate masterpiece, L’Incoronazione di Poppea (The Coronation of Poppea) for 1642-43, premiering just a few months before his death in November of 1643. Incoronazione especially was exceptionally popular, being staged at Naples in 1651. With Ritorno and Incoronazione, Monteverdi brought to his audience a plethora of human emotions portrayed in tear-jerking and belly-aching accuracy.

Unfortunately, Monteverdi’s works soon fell out of the repertoire due to evolving styles and a craze for newer hits. They wouldn’t be revived until the 19th century. However, his contributions to public opera are indubitably profound. The veteran composer had throughout his career developed a musical style which was emulated by many of his pupils, and their pupils after them. Badoaro was not amiss when he said in his letter dedicating his libretto to Monteverdi that “Venetian audiences [had] been deceived by appearances; the emotions they [had]e seen portrayed on stage [had] necessarily left them cold and unmoved, because they were warmed by a painted sun; only the great master Monteverdi, the real sun, radiates sufficient truly to ignite the passions.”[vii] Monteverdi, in his last few years, had kindled a roaring fire for opera in the heart of Venice.

Notes

[1] Recitative is a style of delivery involving ‘sung speech;’ the rhythms are freer and resemble spoken text rather than actual music

[2] The music of Nozze is lost, except for the libretto. Ellen Rosand analyses it as the second in a ‘trilogy’ of Monteverdi’s Venetian operas, between Ritorno and Incoronazione in her book Monteverdi’s Last Operas– A Venetian Trilogy (see citations).

Citations

[i] Edward Muir, The Culture Wars of the Late Renaissance– Skeptics, Libertines, and Opera (2007), 22.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Ellen Rosand, Monteverdi’s Last Operas– A Venetian Trilogy (2007), 7.

[iv] Tim Carter, Monteverdi’s Musical Theatre (2002), 238.

[v] Ellen Rosand, Iro and the Interpretation of “Il Ritorno d’Ulisse in Patria” (1989), 142.

[vi] Ibid., 159.

[vii] Rosand, Monteverdi’s Last Operas, 7.

Edited by Maia Driggers, editor of Music History

Cover art by Lily Agnacian