Kaleidoscope: canny and uncanny.

With Kaleidoscope, Siouxsie and the Banshees evolved beyond their punk origins and into something markedly stranger.

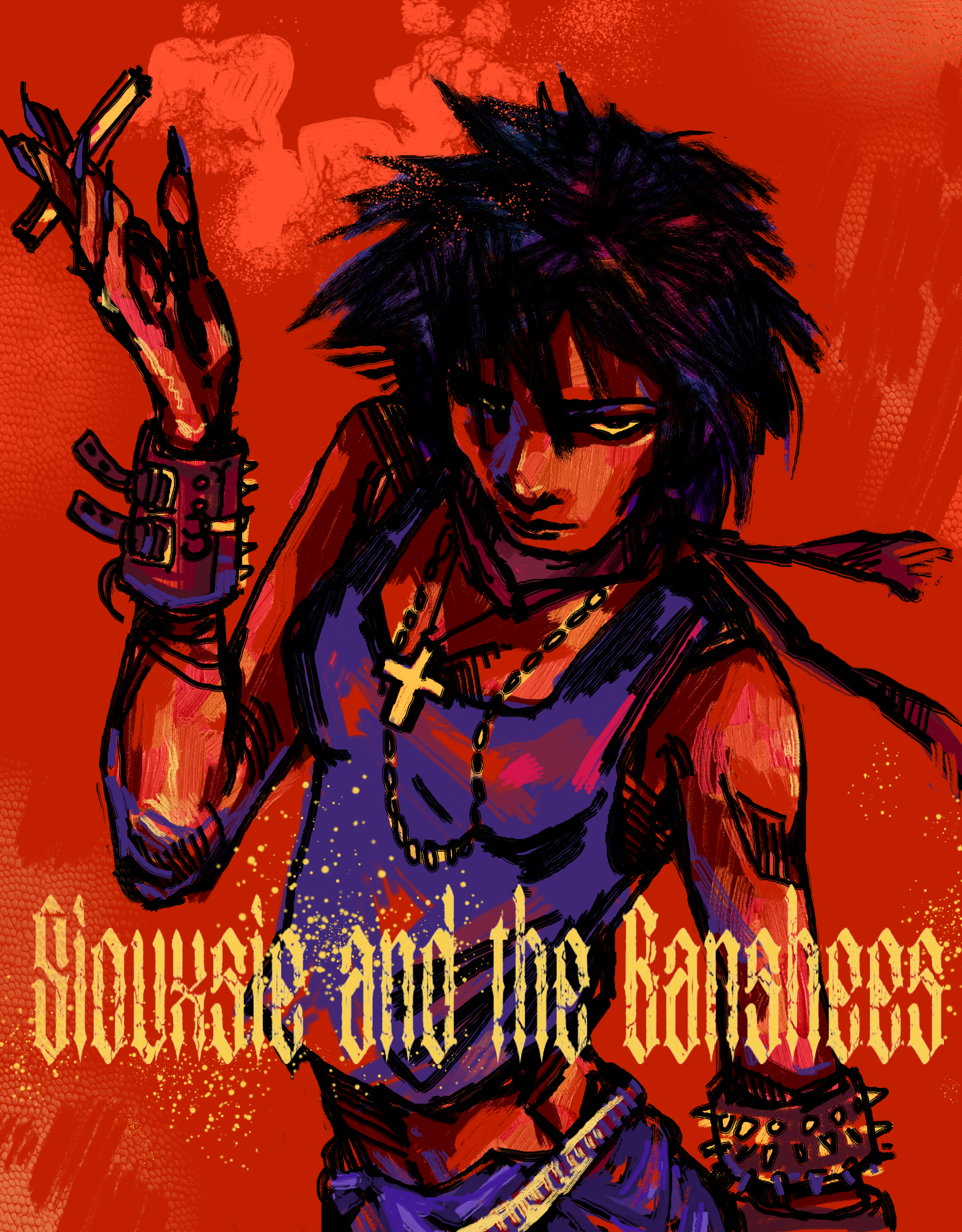

art by Annaelle Le Guellec.

The end of the beginning of Siouxsie and the Banshees was a knockout punch. At a record signing in Aberdeen during their 1979 Join Hands tour, creative tensions and personal differences came to a head when Siouxsie Sioux clocked guitarist John McKay. Sioux had planned on firing him and drummer Kenny Morris after the tour, but she sped things up—and halved the band—right before a scheduled gig. "If you have one ounce of hatred like we had for those two arty ones," she told the Aberdeen audience, "you can kill them in my name." As various punch-ups after the split can attest, she was dead serious.

With half of the Banshees gone, a change in their style was inevitable. They had found success with McKay and Morris: both artistically with The Scream and Join Hands, and on the charts with the top-10 single "Hong Kong Garden." McKay's distinctive angular guitarwork and Morris's tribal drumming had formed the backbone of the band's sound—arty indeed, but too artful to discard so artlessly. Regardless, Sioux and bassist Steve Severin pushed on, fueled more by spite than cash. The band’s corpse continued to tour with the help of The Cure, their support band (Robert Smith played one set for his band and filled in on guitar for the Banshees), until Siouxsie collapsed in the middle of a show. It was at this point, bent to breaking, that Kaleidoscope would take shape. First, though, they needed the personnel.

As one of the biggest alternative bands in Britain at the turn of the decade (The Art of Darkness: The History of Goth, John Robb), the Banshees had the pick of a very talented young crop of musicians. As punk continued to develop at the end of the '70s, teens who couldn't play an E major on the guitar evolved into adults who could play Page, if they really wanted to (they didn’t). Among them was John McGeoch, of the band Magazine. Performing on hits like "Shot by Both Sides" and “The Light Pours Out Of Me” to critical acclaim, McGeoch was at the vanguard of the post-punk movement. By 1980, relations were strained between him and the rest of the band, so when Sioux came knocking, McGeoch was happy to jump ship. Equally skilled was Budgie, who gained prominence as the drummer on The Slits' 1979 album, Cut. Budgie had filled in on drums for the 1979 tour after Morris's departure, and impressed the band enough to be promoted to permanent member.

With the band reformed, a statement of intent was in order. "Happy House," released as a single for their upcoming album, duly provided. Where before the Banshees had been a muscular band, overwhelming with ice-sharp dissonance and sheer feedback, here they were more subtle. McGeoch's lead is thin and catchy, with a pop sensibility that would not have flown in the band of old. Severin’s melodic baseline gives heft to the riff. It is Budgie's off-kilter drumming, however, that bends the song through the funhouse mirror—here whispering below the riff, there galloping through the chorus. The effect is unsettling, as any song about a mental institution should be.

Many of Sioux's songs were grounded in strange places and happenings in the real world, to the point where she would collect morbid clippings in the newspaper to use as material. "It's all there in The Sun," she insisted, and indeed, earlier songs like "Placebo Effect" and "Overground" address the fundamental strangeness of societal mores that are taken for granted. The Banshees' split did not change this. In "Happy House," Sioux sings from the perspective of a patient, her protestations that they're "all quite sane" convincingly conveying the opposite. If the object of a song is to unify the lyrics and composition into a single impression, then "Happy House" was an unqualified success.

The B side to the single, "Drop Dead/Celebration," was no less of a message, being a vicious takedown of the band's deserters. Subtlety is traded for lines like "Drop dead!/You stinking little creep" and "You're so pathetic/An insipid, dried up slug," over guitars that mock McKay's own. The effect is more comical than anything (and McKay himself is known to have enjoyed the song), especially in contrast with the A side, but it is important nonetheless because it represents the ecstatic burial of their old identity. The Happy House single is a reflection of where the Banshees were, and a projection of where they would be.

Kaleidoscope was released in August 1980, less than a year after Siouxsie and the Banshees became Siouxsie and a Banshee. It is a good title for a record, vibrant and punchy, and it is also a good title for a record that is vibrant and punchy. The Banshees were morose, but they were also glam—after all, Sioux began her musical life as a Bowie fan and met Severin at a Roxy Music gig (Robb). Rather than deriving her drama from then-esoteric philosophy and pseudoscientific Martians, however, Sioux's focus was on the latent strangeness of the world she lived in. This is most clear in “Happy House,” but nearly every song is grounded in reality. “Christine,” the album’s other big single, tells the story of Christine Sizemore, a woman famous for her dissociative identity disorder. Some of these personas, such as the "strawberry girl" and the "banana split lady," were named for the foods that they would eat exclusively, and are quoted in the chorus. Christine is caught in many minds, fractured through a kaleidoscope like the band itself. The B-side, “Eve White/Eve Black,” takes the former’s conceit a step further, imagining the terror of one personality trapped inside the body of another. “Let me out of here/Oh, son of a bitch,” she wails, and she somehow manages to sell the whole thing. Where “Christine” is cute and fun, a psychedelic soup of swirling noise, “Eve White/Eve Black” is regimented and violent, the subtext made disturbingly clear.

While “Christine” and “Happy House” are about internal struggle, Kaleidoscope is also concerned with external struggle, both of and between humans. “Trophy” personifies the mounted animal heads hung on the wall of many a rich hunter, taking cues from works like The Most Dangerous Game to imagine humans as the hunted. With lines like "Taken to the wall to be hung/On the wall," Sioux seems to ask, scornfully, what the point of such gruesome mementos is. It represents the band at their best, blessed as it is by a unique Budgie beat and two of the greatest riffs McGeoch ever wrote. The album’s closer, “Skin,” covers a similar theme of killing animals for their fur. To the creatures she orders, "Give me your skin/For dancing in," and to the humans she sneers, "But you know what I mean/There's too many of them." Her rage is made tangible by drums boiling beneath and guitars droning above, a perversion of the formula Neu! pioneered. For this, as well as “Clockface” and “Paradise Place,” guitar duties were taken up by former Sex Pistols guitarist Steve Jones, whose proto-shoegazing style brings an aggressive release that contrasts with McGeoch’s tense leads.

Siouxsie Sioux once said that she considered the Banshees to be gothic but objected to the term “goth.” It’s a bit of a joke at this point that nearly every band that helped to spawn the goth subculture has repudiated the term at some point or another, but it also makes a lot of sense for the Banshees. They weren’t inspired by goth bands because there weren’t any, and they saw their successors (like the perennially ironic Sisters of Mercy) as pantomime versions of themselves peddling “tacky harum-scarum horror” (Robb). In contrast, they took much of their lyrical inspiration from the gothic literature of writers like Poe and Shelley, and their atmosphere from Hitchcock films and contemporary horror. For The Scream, Siouxsie played McKay and Morris the soundtracks to Psycho and The Omen to give them an idea of the effect that she wanted to create. While later gothic bands fell fully into camp, then, the Banshees played their influences straight—especially in Kaleidoscope. “Tenant,” for example, is suspense in aural form, tinny hi-hats and throbbing bass delivering unnerving tension as Sioux sings of squatters creeping through an abandoned house. The use of sound effects—a scratch on the guitar string, a loud shush—is more cinematic than musical, with unusually concrete imagery (“Forty watt bulb/Swing from a light cloud”) doing the screen’s job. While “Tenant’s” tension dissolves into nothingness, however, the instrumental “Clockface” accelerates towards overwhelming intensity. More than any other song on the album, it is dynamic, the drum patterns constantly changing, the many riffs trading places like an out-of-control merry-go-round, all while the bass thuds into oblivion. If “Tenant” is the buildup, then “Clockface” is the climactic scene.

In the wake of the split, the Banshees discovered a penchant for experimentation. Earlier records like The Scream and Join Hands were aesthetically coherent and very much grounded in punk, but Kaleidoscope marks a sharp break with its stylistic trappings. “Lunar Camel” jettisons most of the band’s personnel for a synth and drum machine, and, while abortive, it is an interesting little experiment. More successful is “Red Light,” which refines and distills the Banshees’ new approach. Lyrically: a withering look at the modeling industry, deriding self-objectification. Musically: a drum machine, a stark four-note synth melody, and little else. Cinematically: a flash of the camera bulb keeping time, the slow build of Budgie’s drums keeping tension. The essential components of a Banshees song are present but are twisted into something completely new—a song that prefigured the coldwave that swept continental Europe later in the decade.

Kaleidoscope is a document of the uncanny in this world, and a document of the change within the band that created it. Given the moment and given the material, Kaleidoscope stands out as the Banshees’ strangest album, sounding nothing like what came before and little like what followed. Amidst the upheaval, however, their character shines through.

edited by Aidan Burt.

art by Annaelle Le Guellec.